In a few months you'll be hearing quite a bit about The Tempest. Based on the director and her proven results with Shakespeare, in both theater and in film, I have little doubt it will be one of the great films of 2010. Time will tell, but Julie Taymor has already shown what happens when she tackles a screenplay and directs a movie for Sir William. She directs with the kind of fire and insight his works need to relay the furious and compelling nature of his emotive, astonishing language.

Not that I'm a Shakespeare aficionado, because I'm not. I readily admit I'm nowhere near smart enough to try and cop to that. I do, however, see more movies than most and I recognize sheer ambition and swoon when it comes my way. Titus is proof of what happens when Shakespeare lands in daring, ambitious hands. It is riveting to behold -- gargantuan, chaotic: FULL ON. I watched it again recently because I am excited for The Tempest, but what I found in Titus was the same brilliant work I saw years ago.

A little boy with an "unknown comic" paper bag over his head plays at a crowded kitchen table stuffed with all his crazy toys. A blaring TV with nothing in particular fills in a noisy background as his playing voice quickly rises, drowning out the blaring TV, turning violent. It's almost as if he suddenly hates the toys and needs to rebuke them for their sin. They, too, are out for blood and want to fight -- fight with each other and with him. He screams at them, pours his food all over them, crashes them into one another and his dinner. A toy soldier scratches at the surface of the table trying to crawl away in fear.

The boy is on a rampage now. Violence erupting his small being spills into the reality of the room, shaking the foundations of the whole house. The violence becomes too much as it pounds and pounds.

He realizes it has come to life. The house may very soon crumble. The growing, dark setting overwhelms him -- he is panicked at the thought of the toys and the violence he has created. The room shakes and finally explodes as he covers his ears in fear.

He is whisked away and carried down a hole ala Alice into Wonderland by a clown that doesn't look like a clown. Down the hole he goes but not before we see his saddest look, and tears streaming down his scared face. Did he really create this violence? Could his imagination become physical? Has it come back to haunt his very play? Is he innocent, as we might think, just a child doing what a child does, or has he brought malevolent harm that he wishes he could take back?

Down the hole he goes into the Roman world of Titus Andronicus, who will introduce him to similar perils, albeit political. The child will be a silent observer, a mute witness for the first half of this story, to blood upon unrelenting blood, until he can take it no more and must enter the story himself. He becomes little Lucius, the grandson of Titus the hero, the general who has come home with the spoils and loot of war, only to be spoiled and looted himself.

Is there a better way to launch the introduction to arguably one of Shakespeare's most disturbing and dark works than with this innocent bystander with a history of his own -- a child, no less, carried to Rome to observe? And when observing the most hideous and corrupt actions in human nature, could anyone better deal with resolving the violence he has seen?

Bringing the silent observer the way Taymor does and then turning him into the character of Titus's grandson is an affecting choice in the midst of this blood-thirsty world. We need someone there to remind us of innocence. We need someone there that can watch, while we observe.

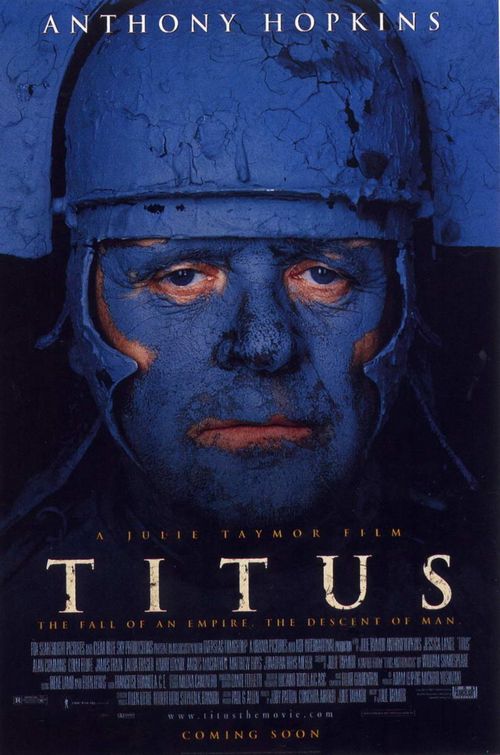

In a matter of hours, in some questionably wrong but understandable choices of allegiance, Titus (Anthony Hopkins) goes from war hero to outcast, dispossessed from his country, cut off from his people and his family. Maybe for the first time in his adult life, he is utterly isolated, completely alone. To make matters worse his enemy Tamora, Queen of the goths (Jessica Lange) is strangely promoted from slave to Queen of the empire -- she will easily infect young King Saturninus against Titus, and his sons and daughter are going to pay the ultimate price in revenge.

In terms of the rest of the plot, it's the story of their feud -- it's the Hatfields vs. the McCoys dressed as warring politics in ancient Rome. In terms of Shakespeare and the way he tells the story -- oh! The language! I cannot describe how amazing it is. Time doesn't make any of this old language grow more "old," but greater, more rich, more poetic and able to dig in. It connects even with modern audiences and contemporary ears. This is a story that was originally read for its language -- you will be richly rewarded if you watch with the subtitles on.

In terms of what Taymor has done with all this, her approach is very similar to Baz Luhrmann's Romeo + Juliet, which starred Leonardo DiCaprio and Claire Danes only a few years before. The films have in common a blending of traditions -- they each carry an ancient/modern approach to the screen. But while the guns and shooting in Luhrmann's film come off as vain and gimmicky, the vehicles and costumes and the whole design of visuals in Titus are always an allegory that's tangible, within reach. It is as entertaining to look at as it is to consider.

In fact, I know I've talked about it already a hundred times this year, but going back a decade and watching Titus brings back memories of last year's masterpiece, Vincere. It is that grandiose, that daring, it is that willing to take risks, and has that ability to believe in itself (and achieve in itself!). These are all the reasons it brings success in such large measure. Even the imperial Roman art and neo-classical architecture are where the two films relate so well. Characters in both films, too, are intoxicating, as is the camera's ability, which is unyielding.

But Titus is written by Shakespeare.

And that is clearly what sets is apart.

Titus Andronicus, as played by Hopkins and Lange, is an incredible spectacle of blood-lust and power -- and the child that was so frightened of the violence he created brings one of the best, most artistic endings imaginable.

I'm so glad I was able to see this again, and now I'm more excited than ever for The Tempest. We'll see how Helen Mirren's female Prospera will add to the Taymor/Shakespeare tradition!

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment

I like to respond to comments. If you keep it relatively clean and respectful, and use your name or any name outside of "Anonymous," I will be much more apt to respond. Spam or stupidity is mine to delete at will. Thanks.